Custom Search

|

| boat plans |

| canoe/kayak |

| electrical |

| epoxy/supplies |

| fasteners |

| gear |

| gift certificates |

| hardware |

| hatches/deckplates |

| media |

| paint/varnish |

| rope/line |

| rowing/sculling |

| sailmaking |

| sails |

| tools |

| join |

| home |

| indexes |

| classifieds |

| calendar |

| archives |

| about |

| links |

| Join Duckworks Get free newsletter CLICK HERE |

|

|

| Out There |

by Paul Austin - Dallas, Texas - USA The Archer of Norway |

|

The great designer of Norway's rescue ships was Colin Archer, a man who seemed to have three lives. He was born into adventurous times, a quiet man surrounded by falling fortunes, sudden wealth and colorful travel. He wasn't even Norwegian. His family lived in Perthshire, Scotland, earning their way for several generations as glovers. They were members of the glovers' guild of Perth. One of them served in Cromwell's army in Scotland, at the same time that Shakespeare's father was a glover in middle England. Colin Archer's mother was Julia Walker, from a small fishing village named Leslie, Scotland. Her family had been island dwellers on the Hebrides but, surrounded by the sea's crashing waves, they moved to Leslie to farm and operated a tannery. Turning the warm soil, planting in the spring, dirty hands and bent backs but clean souls. Make do with what you're given and be satisfied. They were staunch Presbyterians, versed in predestination, communion as sign and symbol, the Bible as God's Word, the denial of ornamentation in church. No pope, no king but Jesus; hard work, self-denial, pull your own weight, finish your dinner, be grateful and pray at night and let the fire in the fireplace lay cold by morning. But these were times of change, in which a man had to find whatever he could before changing fortunes ruined him. Colin's father, William, was a man of the outdoors. He became a partner in the firm of Charles Archer and Son, timber merchants in Newborough, near the Firth of Tay, Scotland. Wood ships to bring wood for shipbuilding, predicting how much timber a ship could hold, calculating price, the labor needed, the profit and loss.

But fate sometimes comes mildly and with generosity. William was on a business trip to Norway when he first saw Larvik, a small quiet fishing village with a pleasant promontory reaching out to the sea below a tall steepled church up the hill. The picture of the village seemed to come from within his daydreams, an inward picture that recognized this real place. Even after he went home, he remembered Larvik. Then the years changed. Without the Napoleanic Wars to pack a lifetime of prosperity into a few tense years, depression followed like a cold wind after a squall. It lay across all Scotland. Ships leaned on their bilges at low tide, wood splintering without paint, no market for fish or timber or farmed produce. Men watched the horizon for any new ship, any new day or news from across the sea. William's timber trade dwindled to the point at which a man's children went hungry, bills couldn't be paid, the clang of pots in the kitchen overlooking the sea had a hollow sound. William then moved. He took his family of Julia and seven children across the cold, granite-grey sea to Norway to that beautiful village named Larvik. The year was 1825. His plan was to be a lobster merchant and shipper, supplying lobster for the rich restaurants and hotels in London, Dublin and other cities of the wealthy idle upper classes. Without warships crisscrossing the seas in search of battle, now shipments could be made to the lucrative markets. The man down at the shore with his fishing lugger dragged his lobster nets up over the bulwark side, lobsters sprawling and clawing across his wet, wood deck caught in nets. They were weighted, counted and then boarded on ships with tanks in their holds, often with tiny holes in the wood so that the very cold sea water teeming with tiny marine life could keep the lobsters alive and snipping well until port. William remembered that promontory below the church. He bought the house on the promontory, had it renovated for his family and moved in, a happy brood in a gentle place. Between 1826 and 1836 five more children were born - two brothers and two sisters to young Colin who came into the world of Norway in 1832. In the age before the American Civil War, commercial shipping ruled the waves. Shorelines on maps became more accurate, port depths were increased, roads to those ports were improved, a middle class of merchants not working but supervising men who did the work rose with the years. Shipowners often stood on the docks at Larvik, in top hats and tails with buyers, watching their ships sidle to the posts, trading with a handshake what was in the holds, fortunes changing hands in a moment. Seafaring men from other oceans in bandanas, eye-patches, false legs, weathered hands, sunburned skin and slits for eyes took the night in taverns and tiny rooms, gambling away a voyage worth of coins, watching for another passage, the sound of another foreign port, a chance at riches which never came. Shipbuilders' quays often dropped down the the shore right next to chandleries. The ring of bells at the chandlery door interrupted the trade of rope, turnbuckles, barrels, sailcloth, salt and anchors for paper money pulled out of stuffed pockets. A merchant's boy would stare at the square riggers out his upstairs window. Shipbuilders sitting at their drawing desk in tiny offices, a pencil between fingers, would stare at schooners and ketches and cutters coming in the harbor, notching their chins, hoping to get restoration work or repair work from the captains. All of this surrounded young Colin, coming into the world at the peak of wooden ship trade, construction and design. This was a time in which ship designers looked for every knot of speed they could get on a merchant vessel, to get to market before anyone else. Any nuance of hull design was seen and noted by the builders and designers. Often a man was seen standing at the dock, pencil and paper in hand, drawing the bow on some new ship which hadn't docked there before. Was the bow cut away, was it slender at the waterline, did the ship planks flare amidships or have greater deadrise or turn the bilge more gradually than before? Colin's older brothers had been sent back to Scotland, to learn a trade and prepare for Australia. This was because in large Scottish families who sought a new life, Australia was thought to be the idyllic place. While his brothers went overseas, young Colin worked at a small shipyard nearby probably as a ship's helper, watching ship construction and listening to navigation terms and methods. He was good at math. The yard was owned and operated by Michael Treschow, who owned mines of ore. The ships were build and repaired to chug the ore to buyers. This was a wonderful time of a young boy learning of big ships, knowledge he would use much later in life.

Now, by 1850, the first part of Colin's life was to turn into the second. His father meant for him to reach Australia but his brother Tom had left Australia to join the Gold Rush in California. So Colin, with his shipwright tools, sailed from Scotland south on the Atlantic, beating against the Gulf Stream and the Trade Winds toward the Caribbean. As he sailed south, the sky was warmer, the air moist, the thought of the Americas and the Caribbean islands before him. Tales of the Caribbean islands had come to the Old World long ago. Folk tales, exaggerations of gold and treasure, sunken ships loaded with doubloons from the Spanish main, the shipwreck scene in Shakespeare's Tempest, wild stories of fortunes and undiscovered islands, naked girls and pirates prowling Port Royal. Colin's ship sailed on to Panama and then north to San Francisco. He spent two years in the gold fields as a carpenter and prospector. He was a long ways from Larvik, but life was an adventure and Colin sought for his own life. He left the gold fields in 1852, although we don't know if he became rich or not. He sailed out of San Francisco for what was then called the Sandwich Islands, now Hawaii. His brother Archibald had a plantation on Kauai. Evidently, the Archer brothers liked to gather men in putting ventures together. They didn't seem to mind what the product was, as long as it was lucrative. Colin was willing to work, but he didn't stay working for someone else for very long, even if it was his brothers. If gold could not keep Colin in California, then for sure a plantation could not keep him in Hawaii. He found passage on a ship for Australia at a time in which square riggers came to Australia on a regular schedule. Colin joined his four brothers in the sheep trade of New South Wales, working the sheep from 1853 to 1861.

What Colin did was scout sheep routes and stations in this new virgin land. He explored the country for feeding grounds and water holes. Every hill was new, every river unknown and uncharted, every mile to be counted as whether it was profitable or not. He sailed with a cargo up the Fitzroy River, Queensland, at a time when it was on no maps, it was not talked about in the harbor bars. He took over a station the brothers had laid out. Maybe he would have stayed, maybe not. But life came after Colin in 1857. His father was advanced in age, his health was failing. First, Charles Archer left Australia to be with his father. But by 1861, with the Civil War in America, Colin was called back when his father's life was coming to an end. And then Charles died late that year. The next year, Colin's father died, leaving him with the leadership of the family members in Norway. The family had produced wealth, and Colin enjoyed it for a while but he knew this would not last. Manufacturing had grown in England and on the continent, steamships blackened the sky with their coal smoke, the century of sail was nearly past the horizon and a new day was coming. Colin had never lost his love for the sea, so it was to the sea and Larvik's men that he turned. He couldn't leave Larvik, as in years past. Here the third part of his life began. He had no education in ship design, so Colin began on his own. We know that Chapman's famous book on ships with lines was available, as it is today. Colin had plenty of small boats to look at, to study and draw and compare. He knew Norwegians build ships to perform duties, not to race or look rich or be comfortable. Many of the fishing vessels barely had enough room for the crew to sleep, and then they slept on sails hung from bulkheads, hovering over the smelly fish stacked below. So if a boat had a certain form, that would only be to perform a certain duty. The shipwrights who build their own usually had a formula etched on a wood slab about two feet by two feet. This would be proportions of a ship length to width with depth of keel and angle of bow and stern off of vertical. Sometimes a few more numbers would be etched in to make sure the boats behaved both unloaded and loaded with their cargo, whatever it was. Colin saw all of this. He began in his own back yard, building small craft on an inlet called The Bugt, in front of his house. The designs must have worked to the approval of crusty old fishermen and seamen, as Colin then had two berths constructed nearby, facing Larvik.

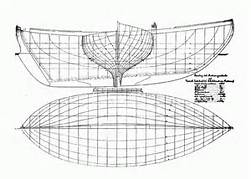

Colin was now 46 years old. With his mathematical talent and gift for ship design and carpentry skills, the boatbuilding venture thrived. His life was settled in at Larvik, although his public reputation and fame would now grow. He married Karen Wiborg, who lived in a town nearby. Colin then build a second house for himself, his ship design work and his new wife. He spent his day drafting at his table, going down to the building sheds where he advised the work with Axel Harman, his assistant, and dealing with the business bills. We don't know how his reputation spread, but his designs must have pleased the Norwegian buyers. Usually fishermen are reluctant to try some new boat. They get used to what they have, no matter how impractical or uncomfortable it might be. A ship is like the old shirt you don't want to replace. Still in 1879 Colin was elected to the Institution of Naval Architects. His technical knowledge must have been aided by his gift for mathematics. In 1886 the king of Norway gave Colin the Cross of the Order of St. Olaf. The honors piled up in the successive years until in 1909 Axel died. When he did, Colin retired the shop, spending his last years answering mail and discussing wave theory. The gentle mind now rested. I could not have written this article without the help of Wikipedia, John Leather's book on Archer (Colin Archer and the Seaworthy Double-ender) and the Archer websites. Fortunately, the facts mentioned in Wikipedia have been verified by Leather's book and the websites. Most of Leather's book are on the designs. While Mr. Leather is certainly qualified to speak on the designs, I am not. So I will do no more than include the lines of a smaller ship in the style of Archer, designed by Mr. Leather. It is 21 feet, with room for two bunks below and a galley. I like it.

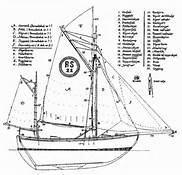

The great inheritor of Archer's style of rescue ship was William Atkin. He designed several ships in the Archer style as cruisers and yachts. The prettiest might be Syltu, 36 feet with marconi sails. This is a relatively fast family cruiser which has plied the ocean successfully.

Paul is also publishing his books on Amazon. |

|