Building Wee Rob

By Paul Kessinger

Building a small, glued-lapstrake craft is a wonderful

experience. Without a whole lot of internal structure, ribbands

or framing, you move to planking quickly. Once you start planking,

the boat grows rapidly into a shapely, tight structure, thanks

to the wonders of indestructible marine plywood and only a half-gallon

or so of epoxy.

With glued lap you get a boat that looks like a boat, with beautiful

curves highlighted by multiple shadow lines. And its real wood

(well, kinda) that you can paint and varnish without constant

reference to a chemistry book.

Here are some thoughts on the building process from the point-of-view

of a basement boatbuilder with an average shop and less-than-average

skills who has just finished a decked “Wee Rob” double-paddle

canoe designed by the glued-lap virtuoso, Iain Oughtred.

Tools of the Trade

Cutting out, cleaning up and adjusting planks to

fit takes the most time in building these boats, so coming up

with a fast way through the process is imperative. I’ve

tried three techniques and find that using a cordless 3.5-inch

circular “cutoff” saw turns out almost ready-to-go

planks. A regular circular saw is heavy and is meant to go straight;

a jigsaw wanders in my inexpert hands and leaves too much work

to plane back “to the line”; but these little saws

seem to take the sweeping curves inherent in small boats very

cleanly. And there is no cord to trip over, cut through or catch

in the saw kerf (I’ve done all three).

A decent plane is an absolute must for building these boats,

but you don’t have to go overboard – catalog quality

Records and Stanley’s are fine. But you must learn to sharpen

and sharpen frequently, because in this 12-foot boat, you will

be planing 144-feet of “lands,” the area where the

planks meet for glueing. You don’t need a sharpening system

or even a grinder. I use an inexpensive combination waterstone

and a Veritas jig to check to the angle between the stone and

blade. If I sharpen twice per land, the plane is happy and the

shavings fly off. If I don’t, one land takes forever to

hack off and I’ve lost all the time I saved by being lazy.

I firmly believe you have to have two battery-powered electric

drills, one with a bit and the other with a driver, available

at all times if you are going to build a glued-lap boat by yourself.

There are simply going to be times when a piece of wood has to

bend a half-dozen ways in three places and slippery epoxy is oozing

all over everything. Tossing in a self-tapping screw or two –

or six – to hold things together until gravity stops trying

to ruin your boat is essential. Changing from a drill bit to a

driver would require the fourth hand that you need when you are

already one short, so having two drill/drivers ready to go really

works – even if your drilling drill is a $19.95 Wal-Mart

special with a cord.

Scarfing – The Bad, the Ugly and

the Good

Good scarf |

Bad scarf |

I made a hash of scarfing plywood panels together

into lengths long enough to make planks, and finally had to redo

them all. I learned three things in the nightmarish experience

that I thought would cost me $300 bucks worth of sapele plywood:

- 4 mil stock needs to be handled one scarf at a time, gently

and precisely. Take your time and sharpen your plane when it

starts to tear the least bit. A flat, stable material such as

plain old waxed paper on your bench and between scarfs works

much better to prevent sticking than crinkly plastic, which

leaves globs of epoxy on the scarf.

- You can’t sand out your mistakes. I used the Norm Abram

approach of a big ol’ orbital sander to try to smooth

up my first rough, ugly scarfs and tore through the veneers

in about 3 seconds, with the epoxy laughing back at me, untouched.

- Even less-than-perfect scarfs really don’t show on the

finished boat. Varnish or paint tends to blend them in, and

I think the small size and dramatic sweep of the planks tends

to run your eyes right past them.

The Gain-O-Matic

Once you’ve built your first glued-lap boat,

you will find spectators coming up to examine the “gains”

– the area where the plank overlaps magically disappear

into the stem and stern. This is done with what’s called

a “disappearing half lap.” You gradually plane and

chisel a half-inch rabbet seven or eight inches long into the

plank that's on the boat. Then you do the same to the inside face

of the plank that’s going to be attached to the boat. Voila,

the planks mate and become as one.

The problem is that hand-cutting gains is a delicate and time-consuming

job – and there are exactly 50 of them on this one little

boat.

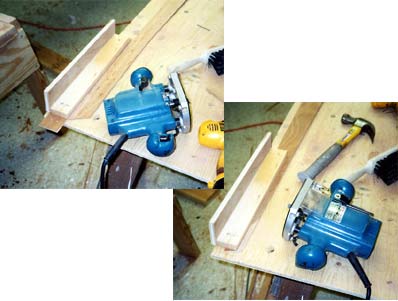

I determined to make a router-based “Gain-O-Matic”

to avoid the butchery that a chisel in my hand usually entails.

All you have to do is plane a piece of stock the width of your

router base from the edge to the bit that matches the length and

depth of the gain. Screw a piece of scrap to the edge of the stock

for the router to ride against. Screw (or clamp) the whole jig

to the plank and rout the outside edge. For the opposite gain,

put a piece of planking stock under the jig and rout the inside

edge. To keep the plank from moving while being routed, I nailed

it to the bench with brads.

Frozen Brown Snot and Other Delights

It is a very reassuring sight to see glue squeezing

out between the lands as you apply clamp pressure. It pretty much

assures a boat that will float. But if you don’t remember

to climb up into the mold and scrape the excess off before it

sets (or bribe your small children to do so), the clean-up process

will take as long as the planking. I think that a Dremel tool

with a rotary rasp is the best way to take off the missed spots.

It’s safer than a scraper or chisel, and (see above) a power

sander should not be allowed in the same shop as 4-mil plywood.

When you clean up the frozen snot squeezeout, any area of the

plywood that’s been touched will turn brown. But I was pleased

and surprised that after a light hand sanding, the solvents in

the varnish I used tended to blend in with the epoxy, and the

ugly brown splotches disappeared.

Torture Not Lest Ye be Tortured

In the United Kingdom, this type of building is

called “tortured ply.” It’s true with such thin

wood, you can twist and torture it down to the molds if you want

to. But every piece of plywood is a little different; every setup

is a little off. If the wood wants to assume a natural shape and

the planks meet in natural curves, don’t try to force them

down to the molds or you will surely get flat spots.

Iain Oughtred is not going to fly over from Scotland and give

you a hard time if your boat is a half-inch fatter than the plans.

If it looks good, it probably is good. If you can’t tell

what looks good, collect stamps.

For More Information

More opinions, pictures and tales of agony and ecstasy

are available at my Wee Rob building site:

https://www.geocities.com/pkessinger/WeeRob.html

|