Things

Managed by Muscles

Before Boat Moves

by R. C. Taylor

(Excerpted from The Mariner's Catalog - Volume 3)

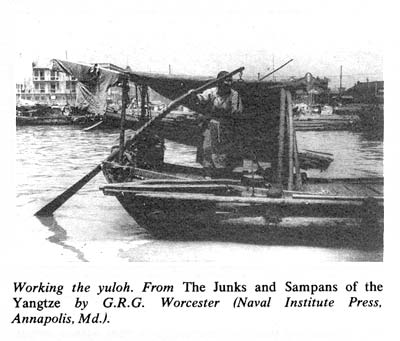

The above heading is a brief form of the Chinese

definition of the yuloh, one of the greatest marine inventions

of all time. It is a sculling oar for small, medium, and large-sized

vessels.

The full definition, as the late Ham de Fontaine

mentions in his piece on the yuloh reprinted on the opposite

page from a 1948 issue of Yachting magazine with the kind permission

of Dorothy de Fontaine and Yachting, is: "The thing on

the boat's sides which is to be managed by strong muscles before

the boat moves." Ham's description and drawing described

the thing well, and here are an additional comment or two.

First of all, we can testify that the thing works.

We used a 10-foot yuloh on our old Herreshoff sloop, a 32-footer

displacing not too much less than 5 tons. It shoved her along

very nicely in a calm at about 2 knots. I say "it shoved"

because once you got her going, the yuloh really did seem to

do most of the work of keeping her going. At any rate, the yuloher

only had to put out a modest effort.

There was always something very satisfactory

about sculling with the yuloh. The yuloh follows exactly the

same path through the water as does the sculling oar) but the

yuloh provides so much mechanical advantage compared to the

normal form of sculling, that it somehow seemed as if the thing

was cheating the basic forces of nature. Of course it wasn't;

it was just taking full advantage of them.

A critical point that Ham didn't mention, I believe,

is the method of attaching the lanyard to the inboard end of

the yuloh. On our 10-footer, the attachment was made not to

a fitting snug up under the end of the yuloh, but rather to

a long, strong screw-eye, whose eye stood 2-3/4-inches out from

the bottom edge of the yuloh's handle. As Ham points out, the

lanyard takes the thrust of the oar, thus relieving the yuloher

of the job of pressing down on the inboard end of the yuloh,

as the unfortunate sculler has to do with his clumsy oar. The

lanyard also keeps the yuloh's blade from diving too deep.

But the lanyard has another important function:

it allows the yuloher to alter the degree of feather that the

yuloh naturally assumes due to the convex shape of the top of

its blade, thus enabling him, with practice, to get the most

out of the thing under varying conditions and particularly at

the end of each stroke. The more the point of attachment of

the lanyard stands out from the yuloh handle, the more a pull

on the lanyard will change the angle of feather of the blade.

A yuloher working alone has one hand on the loom

and one hand on the lanyard. He pushes and pulls the yuloh back

and forth with both hands, but the lanyard hand leads the loom

hand by a bit, particularly at the end of the stroke, when it

swings out quite far from beneath the loom and then swings back

with a quick snapping motion that changes the feather from one

direction to the other.

The degree of importance of the work on the rope

may be gauged by the fact that in China, with two men working

together on a yuloh, one works entirely on the rope. If there

are as many as eight men working on a big yuloh, at least two

would be working the rope. These would be the most skilled in

the yuloh crew: "This latter is a very specialized branch

of the art; the rope-men throw themselves backwards with great

abandon until they lie almost flat on their backs, their opposite

numbers, doing the same thing, bringing them to their feet again."

This last from G.R.G. Worcester, the late, great, English expert

on Chinese watercraft, quoted from his fabulous book: The

Junks and Sampans of the Yangtze.

Worcester mentions that some yulohs have iron

edges worked into the blades. This is to give the blade more

weight and also to give it a sharper cutting edge as it moves

through the water. The blade on the yuloh I had was quite heavy,

being made of oak, but I believe some extra ballast in the blade

would have made it even easier to use.

Worcester shows drawings of six types of yulohs,

some straight and some curved. He describes the Shanghai yuloh

as being curved, with a large blade, making an angle of about

45 degrees with the surface of the water. He says the Szechwan

yuloh was straighter, with a long, narrow blade making a flatter

angle to the water. The former provided more power than the

latter, but the latter gave the boat a bit more maneuverability.

Try this thing. It does take "strong muscles

before the boat moves," but once she gets going, then weak

muscles can keep her moving.

—R. C. Taylor—