|

All of my life, I’ve lived along the banks of the Flathead, a wide meandering river with lots of interesting backwaters and oxbows. My father, who was more dedicated to his “real” job than I, was far too busy (and too financially strapped)

to spend time or money on boats when he could better devote his resources to creating a bigger and better farm. Consequently, during my early years, I spent plenty of time watching boats pass by, but I seldom had the opportunity to actually get out on the water. On the few occasions when I did, I was much taken with the beauty of the scenery, and the serenity and freedom of movement that only being in a boat can provide. to spend time or money on boats when he could better devote his resources to creating a bigger and better farm. Consequently, during my early years, I spent plenty of time watching boats pass by, but I seldom had the opportunity to actually get out on the water. On the few occasions when I did, I was much taken with the beauty of the scenery, and the serenity and freedom of movement that only being in a boat can provide.

I started building boats at an early age, but lacking appropriate tools and materials (or any knowledge of how to use them if they had been available), I had to make do by building crude models, sending them out to sail on their own, and imagining what it would be like to own a real boat someday.

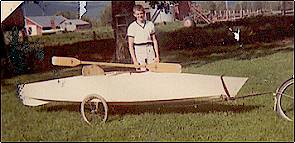

One day when I was 15, I had a chance to go for a short paddle in a homemade stick & canvas kayak. I thought, “Hey, I can build one of these!” Well I did, but it was 35 years before I figured out why the darned thing was stable when sitting dead still, but invariably capsized every time anyone tried to get to get it up to speed. I tried to correct the problem by attaching a fin on the rear of the “keel”. This made the boat track nicely, but only until it decided to roll over. Had I known then what I know now, I could have solved the problem by simply shifting the seat position about 1’ to the rear. By having the center of gravity too far forward, the bow was forced to plow along, and as soon as a critical speed was attained, it would decide to roll, either left or right, with out warning. It’s kind of like having an ill- formed un-steerable rudder hooked onto the front of the boat. before I figured out why the darned thing was stable when sitting dead still, but invariably capsized every time anyone tried to get to get it up to speed. I tried to correct the problem by attaching a fin on the rear of the “keel”. This made the boat track nicely, but only until it decided to roll over. Had I known then what I know now, I could have solved the problem by simply shifting the seat position about 1’ to the rear. By having the center of gravity too far forward, the bow was forced to plow along, and as soon as a critical speed was attained, it would decide to roll, either left or right, with out warning. It’s kind of like having an ill- formed un-steerable rudder hooked onto the front of the boat.

Four years after the kayak fiasco, I had an epiphany of sorts. I discovered that any pair of ordinary straight boards, bent around transverse spacers (bulkheads or frames) with angled ends,

resulted in a shape that looked surprisingly like a boat, with a proper “sheer line”, bottom “rocker”, and everything. If my youth had included exposure to a few proper dories, I might have noticed this sooner, but this was before the current proliferation of drift boats. The only dory type boats I was familiar with were found in Winslow Homer paintings, reproduced in history books. Aluminum and plywood ruled; fiberglass was being “discovered”. There was very little boat building tradition or knowledge to be found in Montana during the 1960s. Boats simply came from a factory in some other state - end of story. resulted in a shape that looked surprisingly like a boat, with a proper “sheer line”, bottom “rocker”, and everything. If my youth had included exposure to a few proper dories, I might have noticed this sooner, but this was before the current proliferation of drift boats. The only dory type boats I was familiar with were found in Winslow Homer paintings, reproduced in history books. Aluminum and plywood ruled; fiberglass was being “discovered”. There was very little boat building tradition or knowledge to be found in Montana during the 1960s. Boats simply came from a factory in some other state - end of story.

I took my “new” board bending idea, along with a pair of 16’ pine 1” x 10”s and two sheets of ½” exterior grade plywood, and created a reasonably fast rowboat. It was stout enough to bounce over logs and gravel bars all day, but it was tremendously heavy. Luckily, back then, I was young and stubborn enough to maneuver it up to the top of my jeep. Unfortunately, one small miscalculation in the flooding Gallatin River, slammed it into a huge cottonwood stump, splitting all the tarred and screwed seams, and nearly drowning me and the unfortunate young lady who had agreed to take a scenic boat ride that day. The boat was ruined, and we lost everything we had except the clothes we were wearing. In hindsight, we were extremely lucky to walk out with only minor hypothermia and scratches.

Six years latter, I couldn’t resist the call any longer, so I built another boat. This one was made from 3/8” CDX plywood, with plywood sides and rudimentary framing, including chine logs, inwales & outwales, and a keelson (though I’d never heard of such terms back then). She was much bigger (18' long x 4' widewith a squared off bow) to carry my expanding family. In spite of the lighter materials, she was even heavier than the wrecked 16 footer. I rowed that big old boat many miles, and enjoyed being able to get out on the water for a couple of years, but the cattle went down to get a drink one day, and they walked all over the bottom of the boat – well it was in their way after all! - and that was the end of my boating until our children were well past their grade-school years. I didn’t like the situation, but I was just too busy raising kids, crops and livestock to do anything about it.

Maybe it was the boat rides our oldest daughter took as a toddler, or maybe it was just a genetic predisposition (or defect?) but, when Megan went off to college, she got herself into the crew program at Gonzaga University in Spokane, Washington. Our first “Parent’s Day” Regatta, with all of those beautiful sleek shells (and an opportunity to actually sit in one for a few strokes), was more than I could stand - I just had to do something, but I wasn’t quite sure what. Buy a stitch & glue plywood kit? The price of the kits wasn’t so bad but, by the time you include a drop-in rowing unit, a pair of high tech oars and freight, the total bill was too much for a small-time farmer with three kids in school. Purchasing a factory built shell was not even a consideration. Having once sat in the real thing however, I knew anything made of heavy construction-grade plywood would never be good enough again. I needed a better “plan”.

I’ve always admired cedar-strip canoes, and I had long been intrigued with the idea that a canoe could be made to go faster and farther using oars. (I used to be able to beat ordinary canoes with the heavy plywood boats.) I had no idea whether anyone else had the same idea or not, (I’d never heard of Adirondack Guide Boats or Whitehalls) but I was beginning to form an idea. After several months of pestering anybody I could find who might know something about wood-strip and fiberglass construction, then ferreting out some sources for fiberglass and epoxy, I was on my way… Well, sort of.

A wood strip wherry, with enough capacity to carry one or two passengers, and enough room for one or two rowing positions, seemed like a reasonable thing to build. The only trouble was, I still didn’t know much about boat construction or the first thing about actually designing one. The result was something like a low freeboard, decked canoe that we afectionately call the Beast.

Not realizing they were unnecessary, I built the Beast with laminated oak ribs every 20”, and aggravated the situation by gluing the 1½” redwood strips directly onto the ribs, thereby creating a terrible mess when it came time to ‘glass' the interior. Not realizing they were unnecessary, I built the Beast with laminated oak ribs every 20”, and aggravated the situation by gluing the 1½” redwood strips directly onto the ribs, thereby creating a terrible mess when it came time to ‘glass' the interior.

Another problem was that I’d never even heard of the term “fairing” (as in working surfaces down to a fair curve BEFORE applying the ‘glass) so, by the time I’d partially filled some of the myriad hollow areas of the exterior with epoxy, and slopped overlapping patches of ‘glass into the interior, I had created a rather lumpy (but extremely strong) monstrosity, weighing something like 180 pounds. She rows and tracks okay, and she bounces off of solid obstacles with no apparent damage, but, whether I pull as hard as I can or just cruise along, the Beast will only go somewhere between 6 and 8 mph. Pulling harder will not make her go any faster; it only succeeds in pulling up a bigger wake.

Beast is a useful boat – stable, with a 37” beam, and virtually indestructible – but I wanted to go faster. The best feature of this boat was that she provided me with an education about what works and what does not. Another thing that happened was that quite a number of folks complimented me on my “cool” boat, flattering my ego. Of course, those that knew better remained somewhat less effusive, providing an important clue that there was plenty of room for improvement. Beast is a useful boat – stable, with a 37” beam, and virtually indestructible – but I wanted to go faster. The best feature of this boat was that she provided me with an education about what works and what does not. Another thing that happened was that quite a number of folks complimented me on my “cool” boat, flattering my ego. Of course, those that knew better remained somewhat less effusive, providing an important clue that there was plenty of room for improvement.

Along about this time, my wife happened to notice an issue of

"WoodenBoat Magazine", on the grocery store magazine aisle, and she bought a copy for me. In this particular issue (# 131), there was a picture of a truly beautiful Red Cedar canoe, with Yellow Cedar accents, built by Eric Shade in Connecticut. As soon as I saw it, I knew that, besides building something that was very fast, I also needed to create a boat that people would notice and appreciate.

I learned a lot from that first magazine, such as sources for better tools and materials. More importantly, I was introduced to the novel (to me) idea that a boat might benefit from being designed before actually being built. Taking out a subscription to the magazine, I soon found out about things like offsets, buttock lines, sections and, best of all, drawing with a batten and using a fairing board. All of these things seem pretty basic now, but if you’ve never even heard the terms, the concepts can be surprisingly elusive.

Owing to the fact that I’ve not yet found a way to quit farming, I still have plenty of time between projects (much of it spent doing mindless repetitive tasks), which allows my mind to wander along more creative paths. As the spring, summer and fall work of 1997 progressed (and as I studied the shortcomings of Beast), I gradually developed ideas of what I would do next. I also stumbled onto a method of creating some rather unique sheer panel designs (using circular plug cutters and large Forstner bits), which could be used to create patterns just as eye catching as Mr. Shade’s, and yet, not be just another version of what he, and others, had already wrought.

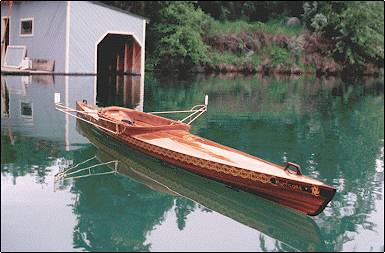

Months of anticipation, and even a bit of planning and drawing, culminated in building Otter over the winter of 1997-98. Otter was specifically designed to do five things:

1. Go as fast as possible, yet be marginally stable, so individuals with limited experience could stay upright; hence the 22” beam (a lucky guess).

2.

Fit inside my newly built 24’ boathouse; hence the 22’ 10” length. (Also lucky, in that it’s about the minimum length that a 22” wide boat can be and still accommodate two full sized rowing positions.) 2.

Fit inside my newly built 24’ boathouse; hence the 22’ 10” length. (Also lucky, in that it’s about the minimum length that a 22” wide boat can be and still accommodate two full sized rowing positions.)

3. Accommodate either one or two rowers, interchangeably, so I could row alone or with a friend.

4. Weigh less than half as much as the Beast, because I’m getting too old to wrestle with boats that are heavier than myself.

5. Look so good on the water that WoodenBoat would put her picture in the “Launchings” section of their fine magazine. This was strictly a vanity thing – I realized a long time ago that I’d never be accused of being pretty – the best that I could do is to create things that are beautiful. (Our children aren’t too hard to look at, but that’s mostly attributable to my lovely wife and various ancestors, other than myself.)

Once in a while, things work out; especially if one makes an effort to identify goals and plan ways to achieve them. Otter managed to meet all five goals:

1. Instead of pulling up a big quarter wave, like the Beast, Otter flies along, making little more wake than a duck. She moves fast enough to pull a tiny “rooster tail” up the sharp rear stem, to a height above the level of the rear deck.

2. She fits in the boathouse of course, and she is also about the maximum that can be safely car-topped. The value of a long waterline (in determining ultimate hull speed) was a concept totally unknown to me at that time, but I did realize that length was necessary to provide load capacity without adding width.

3. Three primary cockpit cross-frames, spaced 31 inches apart, allowed for forward and rear rowing positions for occupants up to 6’ 8”. She may also be rowed in perfect trim, by one person seated in the center, by removing the rear set of outrigger mounting brackets and moving the forward set back one frame space.

4. Every part of Otter is somewhere between ½ and ¼ of the weight of the corresponding parts of Beast (even the oars), yet she is just as strong.

5. I submitted a photograph to WoodenBoat Magazine, and they promptly published it in the “Launchings” section of issue #144.

This was where I got into really deep trouble: People saw the picture, liked the way Otter looked, and started writing to me, asking if there were plans available. There weren’t any plans (except in my head) but I was flattered and foolish enough to decide that there could be. Having never seen a professional boat plan, and never having built anything from a published plan for that matter, I dove into writing and drafting as if I knew what I was doing.

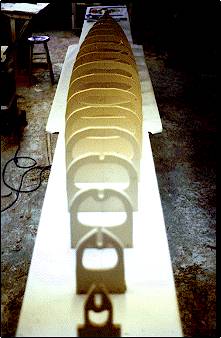

Since I hadn’t bothered to record a lot of important measurements or the critical order of building operations, the first thing I had to do was build another boat (a dedicated single this time). In so doing, I refined the process and the form, found more ways to do just about everything better and lighter, and worked out a second building option for a single-only rowing frame. I was also forced to boil down my design process into logical, repeatable steps. When I did this, I discovered I could design an entirely new hull just by defining a few important lines. By determining half breadths at the sheer, half breadths of the “keel plank” (a solid ¾” thick bottom piece which may be unique to my boats), rocker profile, and the sheer panel flair (which automatically determines the sweep of the sheer line), I could define the entire hull with a short table of measurements, using a constant curve to connect the critical points. This is not quite the traditional method of taking waterlines, buttock lines, diagonals and transverse sections from a half model, and it probably wouldn’t work for a complex wherry or sailboat hull, but I can design a shell or kayak hull in a short time, without a computer program, and be reasonably sure it will be fair.

The biggest challenge was learning how to write clear instructions. When I began the “Plans” project, I naively assumed that I could explain how to build a boat in less than 40 pages of text, and illustrate it with a few simple line drawings. This was because I’d never really tried explaining a process before, and I had never done any technical illustrating. Although the writing and illustrations of the first few pages of my book could certainly benefit from a rewrite, I think they do manage to convey the necessary information. As I continued writing and drawing, my skills did improve, but I’m still working on them three years later. The biggest challenge was learning how to write clear instructions. When I began the “Plans” project, I naively assumed that I could explain how to build a boat in less than 40 pages of text, and illustrate it with a few simple line drawings. This was because I’d never really tried explaining a process before, and I had never done any technical illustrating. Although the writing and illustrations of the first few pages of my book could certainly benefit from a rewrite, I think they do manage to convey the necessary information. As I continued writing and drawing, my skills did improve, but I’m still working on them three years later.

Someday, I may rewrite my entire book and replace some of the drawings with clear photographs, but first I have to use up the remaining copies of the first printing because (as I discovered too late) printing a short run of books can be very expensive. Also, having been through the rather arduous process of writing my first ever book, I’m not nearly as optimistic about doing another in a reasonable amount of time.... Reality bites!

Life, like designing boats, is a continual learning process. Every day, new ideas (and refinements of old ideas) need to be tried out. Each project teaches better ways to do things. Every letter written, every magazine article read, and every conversation with other wooden boat builders is another step toward learning to write and illustrate more clearly, or a clue to better ways to build things. I’ve even learned to type and use a word processor (well, sort of) since first sitting down and scribbling all over some 200 sheets of notebook paper. If I live long enough, I may, eventually, be able to develop all the ideas that pop into my head … or NOT! Ideas happen all the time. Putting them into wood, words and illustrations takes time and effort … but it sure is an interesting worthwhile trip, and I’ve truly enjoyed all the new friends and ideas I’ve encountered along the way!

|

![]()