Custom Search

|

| boat plans |

| canoe/kayak |

| electrical |

| epoxy/supplies |

| fasteners |

| gear |

| gift certificates |

| hardware |

| hatches/deckplates |

| media |

| paint/varnish |

| rope/line |

| rowing/sculling |

| sailmaking |

| sails |

| tools |

| join |

| home |

| indexes |

| classifieds |

| calendar |

| archives |

| about |

| links |

| Join Duckworks Get free newsletter CLICK HERE |

|

|

| The Lumberyard Villain |

by Paul Austin - Dallas, Texas - USA |

This all began when I went to get some plywood for a dingy. But I knew I couldn't get an 8x4' sheet of plywood up my apartment stairs without borrowing Chuck's family helicopter. So I asked the lumberyard villain to cut the plywood in half, 4x4'. If you're wondering why I call the despicable lad a villain, it's because he kept looking at my credit card as if it were chocolate. Anyway, he did the cut, but he didn't get it right. He cut one side in the shape of Jennifer Lopez. So I was short of wood, but not short of laughs when I left the lumberyard. I couldn't build the dingy the way it was designed. After a few months of being, sicklied over with the pale cast of thought, as Shakespeare said, I looked at that sorry and sad plywood, unable to speak for itself. All it could do was splinter my shins. Then I had the thought of building the dingy with all straight sides, a pure box with a bottom. After taking some measurements, I realized I could just make it work. Since I live in a small apartment, I decided to give it a wedge shape, so that if I made it in two pieces one would fit into the other. It would be easy to car-top that way and in my apartment it would be a wide, funky looking bookcase. So that's what I've done.

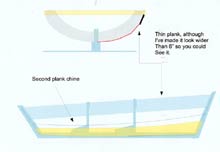

I've learned a few things about building with plywood. 1-There is a boat in your mind, which you can build easily. It might be a Bolger Tortoise, a Oughtred lapstrake, an Atkin flat-bottomed gem, but there is one in there. When you find it, you can build that boat naturally, with no real stress and your own enjoyment. 2-The boat which is easiest to get to the water will give you the most enjoyment, whether it is a curving beauty like the Atkin Vintage or a Gavin Atkin Mouse. You'll use the boat which is easiest to use. 3-Method is madness. Plywood boats can be nailed up without glue, with enough nails. They can be glued up without nails if you can clamp them. Boats with the chines on the outside can be clamped twice without nails or screws, if you have C-clamps. Lapstrake boats can be clenched with just wire nails and two hammers, but you need the laps to be of an angle which leaves you plenty of room to mate one plank with another. Feathered edges can crumble, and paint can flake off an edge which is too thin. With flatiron skiffs you can lay the plywood on the boat's frame, draw lines inside the chines and then cut; this means a flatiron skiff won't cause you to cut pieces too short and waste plywood. They also easier to estimate how many sheets of plywood you'll need. So the method you choose can help you do a good job or it can make doing a good job more difficult. 4-The smaller the boat, the greater the enjoyment. This has to do with worry over cost, maintenance, dock costs and repairs, and even crews. I once read a designer - who had no sense of humor - say every man should have a boat with the same LOA waterline as his height and the same waterline width as the length of his walking stride. So, generally speaking, if you are 5'11" your boat should be about 7 1/2 feet long; it should be 3 feet wide. This particular designer had a small boat he kept for years while he designed 50 footers for other people. Old Captain Nathaniel Herreshoff himself kept a 9 foot flatiron skiff just on the beach where he had his shipyard, to drop it in the water and row across to his home. There is a picture of this skiff in one of the old issues of the Herreshoff Museum newsletters. 5-You can get away with no framework on a lapstrake boat if the stem, keel and sternpost are thick enough to be fastened solidly. The strongest thing you can do is glue two or even three pieces of 1"x4"wood together for the keel, stem and stern. The glue makes them stiffer than they would ever be by the old method of bolts. Then you can use a piece of 1/4" plywood 6" wide around the sheer to hold the top of the frames in place. But you need to have two supports for this plank. One is little blocks 2"x2" on either side of each frame to hold them in place. If the frames are to be removed, you can glue the blocks to the frame and nail the plank into them. The other is a support for the frames glued against the frame where it connects to the keel, screwed on the keel, and preferably 1"x4". Ideally you would have two frames equidistant from the middle of the boat, say 1 foot on either side of the waterline midpoint. Two frames holds the plank bend pretty well. The frames should then be solid enough to put the garboard on. The wider the garboard, the more solid it is, the stiffer it is and the more stationary the frames are. There is an old dory called a Chamberlain skiff with a garboard twice as wide as the other planks. Having done that, with a garboard, a sheerline plywood plank, the stem, stern and keel holding the frames, you can proceed to planking the boat until it's time to remove the 6" sheer plank, for the sheer strake. All of this is relevant only to small lapstrake boats. With longer boats, tension on frames makes it necessary to shore up each frame inside where the planks will go. Also, with longer lapstrake boats, the sheer stringer supports the deck which stiffen the topside planks considerably. The odd thing is that if the frame isn't perfectly upright by an inch or less, it doesn't really matter once the planks are on, sanded and painted. What kills a lapstrake hull is when the planks bend in where they should be straight. If a plank bulges, it can be sanded - up to a point; if a plank sinks it affects the waterflow enough so that you usually have to find the error and replank.

6-You'll see the tiniest imperfection when you build, but once the glue and paint are on you won't remember that imperfection. And once the boat is sailing or rowing or motoring, it won't matter what the style of building is, you'll love being on the water. In truth, every design is a blend of compromises. The flat bottomed boat with the upright stem might cause a wave at the bow but if the stern lifts well, the water will escape easily, speeding up the boat. If the sides are straight upright, it might look like a box but that same sharp chine cuts into the water well when you're sailing with the wind a'beam. With lapstrake, the curving sides looks cool out of the water but those same curved sides are a bit tipsy and the boat will have to sink deeper in the water before stabilizing. A wide-beamed catboat might look heavy but it has less wetted surface underwater than you might think, which is why they can be fast. But that's also why they have centerboards. Schooner rigs and gaff rigs don't head upwind as well as you might want, but with the wind a'beam there is no faster rig per square foot of sail than a schooner (If you want a schooner which can work toward the wind, have the widest point of the waterline 1/3 the distance from stem to stern; then the waterline should straighten out for a straight run to the rudder; then don't put the throat for the gaff too high up on the mast). And if you're trying to escape a thunderstorm, it's better to be making 4 knots at 45 degrees off the wind than 1 knot at 40 degrees off the wind, anyway. 7-A good designer will put a fairly long if a bit shallow keel on a boat for windward performance, but a great designer like Atkin knows how to mate the keel with the sail to get windward performance out of any kind of sail or hull. An example is the ketch Milford where the keel is deep but not large, directly under the mainsail with the gaff's high peak. The rudder responds to the mizzen sail as much as it does to the boat as a whole. So you have high peak, deep keel, chine in the water and large rudder. By the way, this is a great family boat, with the keel easier to build than a deep keel requiring through bolts. Bolger used to say, a deep rudder makes up for design flaws.

8-And finally, build what you can afford, what you will use. Nothing sadder than a wood boat deteriorating in the garage or back yard. Cue the music, Mike, to the tune of St. Louis Blues:

Not everyone around the world has a lake, bay or stream just down the road; let's be grateful for what we have.

|

To comment on Duckworks articles, please visit one of the following:

|

|