Custom Search

|

| boat plans |

| canoe/kayak |

| electrical |

| epoxy/supplies |

| fasteners |

| gear |

| gift certificates |

| hardware |

| hatches/deckplates |

| media |

| paint/varnish |

| rope/line |

| rowing/sculling |

| sailmaking |

| sails |

| tools |

| join |

| home |

| indexes |

| classifieds |

| calendar |

| archives |

| about |

| links |

| Join Duckworks Get free newsletter CLICK HERE |

|

|

| Out There |

by Paul Austin - Dallas, Texas - USA A Sea Bird Day |

|

Although by the 1890s the age of sail was declining, the great shipyards were still thriving. The justly famous Herreshoff yard was stacked with yachts built awaiting launch, yachts being framed, yacht strongbacks laid out, plans draped over tables, and rolls of plans stored on the second floor. In New York the Nevins Yard was thriving, the Story yard was laying keel in Massachusetts and the MacKays had clippers still sailing the seven seas. However, families on the shore could see smoke rising from steamers more and more. This new century of 1900 would be different, and the young generation welcomed it.

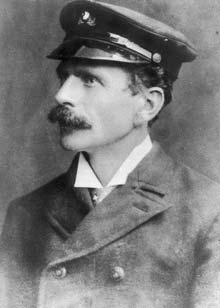

Young Thomas Day had been born in England, but he and his parents came to New York, settling on Long Island. His father became professor of natural science at Normal College in New York. At that time, Long Island was free to roam, to inspire a young boy to imagine what he might do without restrictions. So young Thomas, 30 years old in 1890, began a magazine for everything nautical, called The Rudder. The issue was not producing the magazine, but marketing it. There were several newspapers in New York at the turn of the 19th century and many magazines. In the first 25 years of the new century writers known today such as P. G. Wodehouse or Damon Runyan or Ernest Haycock (the Shakespeare of western writers) wrote for the magazines and newspapers. There were the pulp paper detective novels, badly written but highly sensational. There were local neighborhood rags of 2-10 pages for people of certain neighborhoods. Magazines for the Broadway crowd, Jewish intellectuals, middle class shop-keepers, Tin Pan Alley, the chandlery waterfront and others were sold on the street corner for anywhere from 2 to 4 cents. By 1910 young Irving Berlin was a singing waiter, Al Jolson was the vaudeville star, and this new thing talking pictures was just around the corner. Babe Ruth was a young baseball player on sandlots, and boxing ruled the sport pages. In those days, magazines and newspapers took printed columns and photographs, pasted them onto newsprint and then photographed them. Later, newsprint used faint straight lines to help the men working at tables to line up their columns perfectly. A young man could learn the newspaper or magazine trade in a few days, as Mark Twain did and Day did. As a result, with so much print competition it's fortunate for Thomas Day he was so outgoing. He loved talking about The Rudder. He loved promoting offshore cruising so much the yacht club crowd nicknamed him, 'Offshore Tommy.' Any young boat designer wishing to make a name for himself could do no better than write for The Rudder, including a copy of the lines of his latest creation. Day had already designed a few boats, all of them decent craft. One of The Rudder's columns was, Round the Cabin Fire, which Day wrote about any and everything of which he had an opinion. He was a man sometimes wrong but never in doubt. William Rogers said in 1927 the column ranged from 'the sentimental to the pugnacious.' Day was the first master of the one-liner. Once at a luncheon before the race to Havana, Rogers remembers Day standing before the audience to say this: 'Unless you have been there, far out from the shore, beneath the great dome of the skies at night, a chip floating upon the sea with nothing below you but the ocean and nothing above you but the sky, not knowing what might come on the morrow unless you have been there, you cannot sense the grandness of it. The man who goes to sea learns not to fear but to realize his little consequence, as he sails ever toward the horizon, knowing that the Almighty holds him and his ship in the hollow of His hand. That is enough to know and to trust' (quoted from Wooden Boat magazine, issue 43). In 1898 Day made a promise which he said was made in 'a moment of mental hilarity,' to design a perfect boat for all men, but then he back off of such a claim. However, reader mail would not let him get by with this, till he was forced to go to Charles Mower, a designer and quite sensible man with the middle name of Drown (I am not kidding). Mower was the main designer of the Nevins Yard. He drew the lines of Sea Bird to Day's instructions. L. D. Huntington Jr. drew the construction plans after arguing with Day over putting the ballast inside. The concept was a coastal cruiser any man could build, any man could sail beyond the shore.

Charles Mower and Day needed to spread the readership of The Rudder beyond the yacht club crowd. The middle class was moving beyond the inner city factories. As the railroads nailed the country down going west, so the people followed. Day marched to the drum of working boats which the average guy could build and cruise. So Mower took the lines off Chesapeake working boats, gave them the gaff rig of the schooners and produced Sea Bird. In The Rudder, 1901 these are some of the things Day said about Sea Bird:

However, in 1904 Day wrote in The Rudder that he had replaced the centerboard with a keel. He wrote of two reasons for this. One, the centerboard trunk took up too much space in the cabin. Second, Day had always said in person and in print that inside ballast was better; he wanted to test this out by putting 1000 pounds in the keel. The keel was 10 feet long, putting Sea Bird in the water up to 3'6". He had to put a deeper, broader rudder on for steering and windward work. Day said she was somewhat faster with the centerboard but steers much better with the long keel. However, she does not get herself over big waves as easily. The real advantage of the long keel is that with the centerboard the captain cannot leave the tiller for more than a few minutes; with the keel Sea Bird sailed herself for long hours at a time. This was also true of Joshua Slocum in Spray.

In 1911 Day, Frederick Thurber and Theodore Godwin crossed the Atlantic in Sea Bird. Why did they cross the Atlantic in this 25 footer? Day said later:

As far as we know, no one had ever done that except in boats of much greater length. But Day feared no water, no wind, no horizon. The design was marketed in The Rudder as a boat that would be light displacement (5000 lbs) to ride above the ocean waves. Some reports have it that Day had the centerboard replaced with a ballasted keel just before he embarked, some say they crossed with a centerboard. I could not find any definitive answer, but I suspect they crossed with a keel. What makes all of this memorable is that he actually did take sailing out of the club and into the backyard. He was the transition that would ultimately lead to Philip Bolger and Dynamite Payson. Day was not a designer, but he was a sailer who might have spent more time in a 25 year period on the water than on the land. He wrote extensively about cruising, what to do, what is most dangerous, how to plan for voyages, and the best sense about cruising. Many of us might be reminded that Day paved the way for the Pardeys. As an example of this I will quote from one of his Rudder articles about Sea Bird, published in 1901:

That was written with huge metal steamers in mind as well as 30 foot sailboats. Sea Bird

The design will seem severe to a modern designer, an angled box that fights the water rather than glides over it. It appears to have precious little room, although that is not quite correct. With the V-bottom stretching down, it has sitting room and some living room. The footwell is more comfortable than one thinks. Day, Thurber and Godwin must have been uncomplaining hardy souls, confined to such a small space across the heaving Atlantic. While the Coast Guard might not approve of Sea Bird today for a crossing, modern builds to this design do make wonderful family boats. Paul is also publishing his books on Amazon. |

|