It all began near the end of the 1959 boating season when Henry

Verrier of Coventry, Rhode Island, looked at his 40-foot Eico

cabin cruiser with considerable dismay.

The boat was 11 years old and it's two 135 horsepower inboard

engines were "good in their day, but their day was

over, " as Verrier put it. Replacing the big inboards would

be too expensive, almost equal to the price of a new boat.

About that time, Verrier's friend, Tom Salzillo, was showing

the Johnson movie, "Three For Adventure,'' to some relatives

and friends. The film depicts the crossing of the Atlantic Ocean

by three men in a 22-foot outboard cruiser with a pair of Johnson

50 h.p. motors.

Power Equals Inboards

After the movie, Verrier*s father-in-law, Leo Petreault, commented

that outboard power equaled that of many inboard boats and ought

to do just as good a job.

Salzillo, a Johnson Motors dealer in nearby Smithfield, R.I.,

knew the power of the V-75 h.p. engine and often thought there

were many uses for this power plant beyond single installations

on ski boats and cruisers. Why not apply twin V- 75 outboards

with its 150 horses to move Verrier's 11,040-pound, 40-foot

displacement-type hull?

On paper the plan looked good. Verrier and Salzillo talked

to many knowledgeable people with the consensus usually being

"in theory it should work, but in all practicality it never

will."

But Verrier and Salzillo were stubborn and decided to go ahead.

They had little to lose and much more to gain if they succeeded.

They weren't engineers, but they weren't novices either, since

both were in the marine business. Verrier owns the J & H

Boat Builders of Coventry and Salzillo the Acme Marine &

Supply Co. in Smithfield.

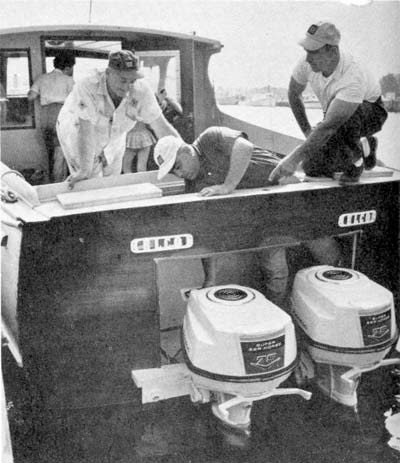

Twin Johnson V-75's power the 11,040 pound

converted inboard boat with ease at speeds in excess of 20 m.p.h.

Began With Sketches

The Rhode Islanders began their project with sketches. Since

neither of them were draftsmen, they spent many long winter

nights laboring over the conversion plans,

The first major problem concerned the transom. The old Eico

had a rounded transom. This meant building a square

section, cutting through and constructing a water-tight well.

The outboards had to be installed with the motor mounts on square

facing and proper drains had to be accompplished to eliminate

the backwash.

Next came the controls. Conventional outboard controls were

not made in long enough lengths. Inboard controls would not

operate on outboards. To solve the problem they devised a unique

linkage between the two types, which consumed most of their

early summer evenings.

Steering presented another challenge. Eventually the steering

was built with rods and linkage. The throttle and shift used

the same system going back to a section just forward to the

transom, where the rods were joined to the con- ventional outboard

controls.

Many Long Hours

Making these adjustments and conversions may seem simple on

paper, but they represented many hours of hard

work and spare time.

Finally in the first week of August, 1960, the day of launching

came. The pair had planned to slip the big boat into the water

quietly, but word leaked out and a fairly large crowd gathered.

It consisted of the serious doubters who had come to jeer, the

half-hearted doubters who had come to cheer, and the just normally

curious.

As the twin Johnson 75's responded to the electric starting

mechanism, the scepticism began to disappear. Within minutes

it was all gone. When Verrier put his hand on the forward throttle,

the big five and a half ton boat began to inch forward slowly.

Gradually it picked up speed, then shoving the throttle fully

forward the 40-foot cruiser responded with amazing alacrity.

Within minutes it was headed out to Narragansett Bay.

Verrier and Salzillo put the boat through many tests that

day. The first thing that surprised them was the speed of the

converted craft. The boat moved at a top speed of 20 miles per

hour as compared with their top inboard power-

ed speed of 18 m.p.h.

Use Less Fuel

But speed wasn't the only surprise. They had reasoned the

outboard engines would be more costly to operate, but were amazed

to discover the two Johnson 75s were burning only 14 gallons

of fuel an hour. In the past, with two 135 h.p. inboard engines,

the boat was using an average of 23 gallons at top speed.

Johnson dealer Tom Salzillo

(center) makes a last minute check m the motor well of the converted

40-foot inboard boat, while Henry Verrier (right) explains to

a friend how the stern of the craft was converted for use with

two John son V-75s

The first day tests were conducted with 10x11 pitch propellers,

which are standard on most Johnson 75 h.p. engines, but much

too large for such a heavy boat. The motors turned over only

3400 revolutions per minute (r.p.m.) with these props, instead

of the required 4500

r.p.m's.

A few days later, Verrier put on 9-inch props to bring the

r.p.m. to 4000 and powered the boat to 21.5 miles per hour.

Verrier has ordered special 8-inch props and figures these propellers

should turn the engines the full 4500 r.p.m/s and produce a

top speed of 23 m.p.h.

One test which had little scientific value, but certainly

added to the pleasure of boating, was putting the boat onto

a beach. This is rarely possible with inboards because of the

deep draft of the props and rudder. With outboards, however,

the only limiting factor is the draft of the hull itself.

Easy To Beach

The displacement hull of Verrier's boat is shallow enough

to allow it to come within easy wading distance of any beach.

The boat can rest in less than a foot of water at the bow, and

21/2 feet at the stern.

The final plus in the conversion to outboards was the increased

space in the boat's cockpit.

Verrier, besides sampling the sweet taste of victory over

doubtful friends' now has a boat that will allow him to cruise

more economically in the future as well as eliminating for all

time the necessity of facing expensive engine replacements before

the end of the life of the boat itself.